In the covid origins debate, Bayesian computations featured prominently as both sides argued their cases at least in part using the language of Bayes factors and Bayesian updating.

The most important question I asked at the debate is whether Bayesian reasoning is a valid approach for resolving questions; specifically, whether it is possible to get the wrong conclusion at the end of a Bayesian argument even if all the numbers that went into your computation are correct. (For more on this topic, see section 3 of my report (pdf).)

However before we can understand the potential weaknesses of Bayesian reasoning or how it can go wrong, we need to understand what it is and how to compute Bayesian updates, which is the goal of this article; while we are here, we also discuss the closely related and famously confusing method of hypothesis testing and p-values. There is a common sentiment that Bayesian reasoning is the “right” way to make deductions or that Bayesian reasoning is “better” than hypothesis testing; this is the same kind of category error as a statement like “cheese is tastier than food”. We will discuss how they relate to each other and why primary science research almost always uses hypothesis testing.

(If you are uninterested in hypothesis testing, you can skip to the third section.)

We are all familiar with the most basic step in logical deducation,

modus ponens:

if is true, and

implies

, then

is true.1Taking

what is intuitively obvious and dressing it up in formal language may

seem counterproductive when working with toy examples, but it has the

advantage of making the statements amenable to algrebaic

manipulation. Algebraic manipulation of formal symbols is much

faster and more reliable when the task at hand is too large to hold in

one’s head. Logical deduction is useful because it allows

for chaining: if

implies

, and

implies

, then

implies

.

The next most basic form of logical deduction is that implies

is equivalent to its contrapositive,

(i.e., “not B”) implies

. I suspect that some people find this less

intuitive because it does not work especially well under uncertainty in

the real world. Suppose, for example, we want to test the claim that all ravens are

black. We could build evidence for this claim by observing ravens,

and verifying that they are black. However that sounds like a lot of

work, so how about an easier plan: observe that “all ravens are black”

is logically equivalent to “all non-black things are not ravens”. We

could build evidence for this completely equivalent claim by observing

non-black things, and verifying they are not ravens! And, we can do that

without even having to go outside and risk encountering an actual raven

(hence this is sometimes referred to as “indoor ornithology”).

This is only the beginning of our difficulties as we stray further from pure mathematics. In the real world, we can never be fully certain of any statement, so the preconditions of modus ponens will never apply. The most common resolution is to augment each statement with a probability, representing our confidence in its truth. What if we try logical deduction now?

Attempting to perform deduction of probably-true statements in the

same way that we did above immediately falls on its face. The root issue

is that it is impossible to perform inference along chains: if implies probably-

, and

implies probably-

, we cannot conclude that

implies probably-

! (Similarly, probably-

and

implies probably-

does not imply probably-

.2In the

terminology of functional programming, this is to say “probably-” is not

a monad,

because for a monad

you can combine

and

to make

(this is the “bind” operation), and you can

combine

and

to make

(this is lifted bind). Equivalently, if

“probably-” were a monad, then “join” would be

, which is to say

probably-probably-

implies probably-

, which is false. The failure of the monadic laws

is what makes probabilistic inference like this useless.)

If we were to chain together probably-true inferences, our uncertainty

compounds until we are left with nothing.

To make discussion easier, let us write to mean “

is probably true” (think of it as saying that

is true-ish), and

to mean “

implies

”. As usual,

means “

or

”,

means “

and

”, and

means “not

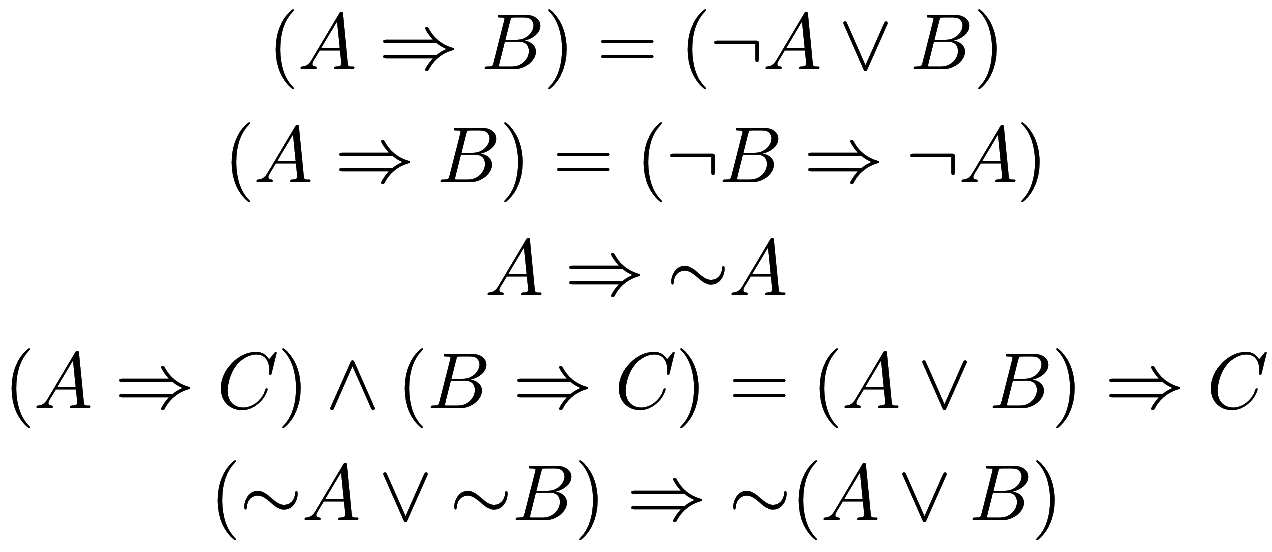

”. For example, one can verify each of the

following:3The monadic laws for

would say

and

![]() ,

both of which are false.

,

both of which are false.

Note that the first statement above can be thought of us the

definition of , the second is the contrapositive, and

the third is one of the axioms of

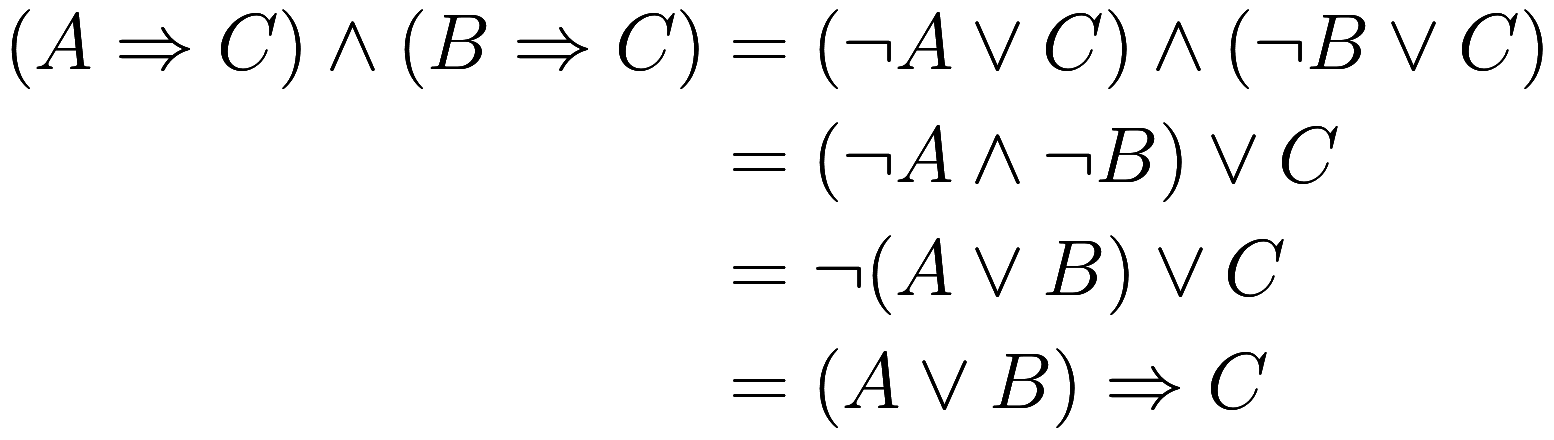

. Before we move on, let us prove the last two

statements. To show the fourth statement, we have

where we have used the definition of three times and basic properties of

and

.

For the fifth statement, we have ![]() , and

likewise

, and

likewise ![]() , so by the fourth

statement the conclusion follows. Note that the converse (i.e., flip the

direction of

, so by the fourth

statement the conclusion follows. Note that the converse (i.e., flip the

direction of ) is false: it is possible for

to be probably-true, but neither

nor

is probably-true.

Let us return again to the contrapositive, which says that if then

. We would like to use

to make a similar statement, that if

then

. This is false

(e.g., if

and

are true, but not

nor

, then the antecedent is true but the

conclusion is false4You

may recall that in ordinary logic we can test the validity of statements

using truth-tables: that is, tabulate every combination of possible

values of true and false for each variable, and then verify the claim

simplifies to “true” for each combination. We could do something

similar, but now each variable has three possible values: true,

probably-true but false, and definitely false. Indeed this technique

successfully disproved the statement here. However I am not sure this

could be used in general, because of the existence of expressions like

and

and

which cannot be simplified into

depending only on the values of

and

.). However, a weaker form of the

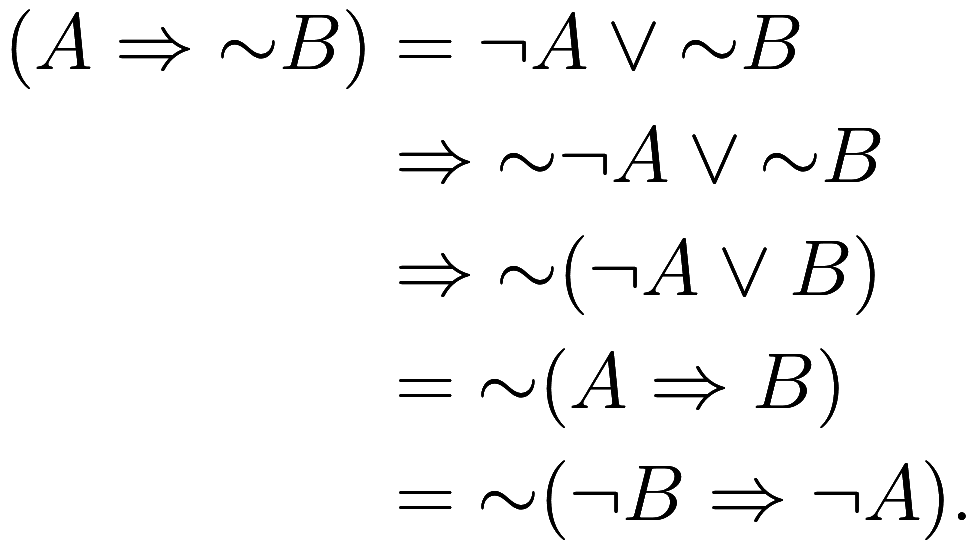

contrapositive is true: if

, then

. Let us prove

that. First, since

implies

, therefore

implies

. Therefore

where we have used the various properties from the list of examples above.

How is this useful? Suppose we have some item whose truth is of interest, but we cannot

directly observe

. Instead

has some consequence,

, which is observable. If we observe

, then we can conclude

.

Of course the real world is rarely so generous as to have certainty,

so rather than we only know the weaker consequence

. Now from

we cannot conclude

, but we can probably conclude

, as we have

. This is not to

be confused with definitely concluding

, which would be

.

This is exactly the formula used in hypothesis testing. We have some

unobservable claim, , called the null hypothesis. To test

, we build a statement of the form

; this process will be

explained in more detail shortly. We then perform an experiment to

measure

. If we observe

, then we can probably conclude

: we reject the null hypothesis at some

confidence level, representing a false negative rate.

We see from this the two main sources of confusion that arise in

hypothesis testing. First, to make this deduction we must observe . If we observe

then we can make no deduction (we “fail to reject

the null hypothesis”), just as if

and

then we gain no information about

. Second, even if we do observe

, we do not conclude that

is probably false; instead we probably

conclude that

is false. These sound very similar but this is

the distinction between

, which is true,

and

, which is false.

It is common for people to mistakenly interpret the p-value as the

probability that

is true; but instead it is the probability of a

false negative if

is true.

Time for the messy bit: how do we construct a statement of the form

? That is, we need to make a

choice for

. As an example, suppose we pick a random number

from 0 to 1, and say that

is the observation that the random number is

bigger than 0.05. Then

where

means “with 95% confidence”. If we observe

, that the random number is smaller than

0.05, we can reject

at a 95% confidence level.5Obviously you should choose the desired

confidence level for your application, and not blindly follow the

traditional choice of 5% error rate, but for purpose of our discussion

it is fine.

As an example, let us say that is the hypothesis that a certain population has a

mean height of 2m and standard deviation of 0.1m. Using the choice for

above, then

is true where

means 95% confidence. If we perform the

experiment we either observe

or

. If the former, we deduce nothing; if the

latter, we have

at 95%

confidence, which we express as “rejecting” the null hypothesis

.

Obviously this is not a great choice of , as it has no relation to the underlying claim

that we want to test. Our approach has a 5% false

negative rate: there is a 5% chance of us rejecting

even if it is true. We also have a 5%

true negative rate, and have a 5% chance of correctly rejecting

if it is false. Our goal then is two-fold: we

want to choose a

such that

according to some desired

false negative rate, and conditional on maintaining that false negative

rate maximize the probability of observing

if

.

The task of choosing such a is usually broken up into 3 steps: choosing a

test statistic, calculating a p-value, and choosing a

false error rate (the threshold for the p-value). Frequently there is an

obvious choice for

that is the mathematically best way to

distinguish the possibilities

and

, for a certain collection of observations;

other times it is less obvious what the optimal choice is, or if there

even is one, and we just have to pick something that seems good.

Different choices for

correspond to different statistical tests; one is

not more correct than another, but one may have greater statistical

power for the same significance threshold, and therefore be more

likely to reach a useful conclusion for a given dataset.

Using again that is the claim that a population has a mean height

of 2m and standard deviation of 0.1m, we will make a more sensible

choice for

. To have any chance of progress, we need

observations that relate to

in some way, so let us suppose we have access to

a random sample of members of that population, and can measure their

heights. Thus we have as data some collection of

numbers

representing these heights; these

are random

variables,6Formally a “random variable” means “a value

randomly sampled from a probability distribution”. in that

each time we perform the experiment we may get different values for the

, and we suppose they are iid.

Depending on our application, we might have much more complicated

observations, including non-numerical data.

A test

statistic is any real-valued function of the observations.7Well,

technically that is the definition of a statistic. A test

statistic is a statistic that is useful in hypothesis testing. Also it

doesn’t really have to be real-valued; it just needs some

ordering. We want to choose a test statistic that is

informative about whether is true or false. In this case, the obviously

best test statistic is the sample mean:

![]()

Next, we calculate a p-value. A test statistic is a random variable

(because it is a function of random variables) and therefore follows

some distribution. We want to choose our test statistic in such a way

that if is true, we know the distribution the test

statistic follows: in this case,

is approximately

normally distributed with mean 2m and standard deviation

. The p-value is found by

normalizing a test statistic to be uniformly distributed in the range 0

to 1, assuming

is true. We do this by computing the cdf

of the test statistic and applying it to the observed value of the test

statistic; that is, we compute the percentile of the test statistic in

its distribution. (We will discuss one-tailed vs two-tailed tests

later.)

Finally, we choose a threshold such as 0.05, and is the observation that the p-value is greater

than 0.05.

Thus, if is true, the p-value is a random variable

uniformly distributed in the interval 0 to 1, and therefore there is a

95% chance of observing

. That is,

, from which we deduce

, as desired: our

test has a 5% false negative rate. However now we have improved on our

previous choice of

. If

is false, the distribution of

is not what we calculated

above, and therefore the p-value is not uniformly distributed

from 0 to 1. Hopefully the p-value strongly favors values below 0.05 –

if so, we will have a high true negative rate (and so low false positive

rate).8You are welcome to, say, suppose the population

has a height mean of 1.5m and calculate the distribution of

and

under that assumption; if

is large enough, the p-value will be strongly

weighted towards 0.

While historically hypothesis testing was intended to give a reject/fail-to-reject binary outcome, as described above, in practice one usually reports p-values directly.

So far we have been staying close to propostional logic, with a bit

of uncertainty mixed in. As we change course to look at Bayesian

reasoning, we will fully accept the probabilistic nature of our

computations. From now on we are using the letters ,

, …, to represent events, with the symbol

to mean the probability of the event

.

Suppose you have two exclusive events9In

probability theory, an event is a statement which has a

probability of being true. We assume events follow certain rules, such

as if and

are events then there is an event called

, representing that both

and

are true, satisfying

![]() .

. and

you wish to distinguish. Unfortunately we

cannot observe them directly; instead we make some sequence of other

observations

.

If one of our observations were, say, incompatible with

, then we would be done; by simple deductive

reasoning we could say “

implies

;

; therefore

”. Instead each of our observations are

consistent with either

or

– but, critically, not equally so.

We measure the degree of consistency with the conditional

probabilities10The

symbol

, read “(the conditional) probability of

given

” is defined as the ratio

![]() .

. and

. From this information it is a simple

application of Bayes’ Theorem

to compute

, and repeated application to get

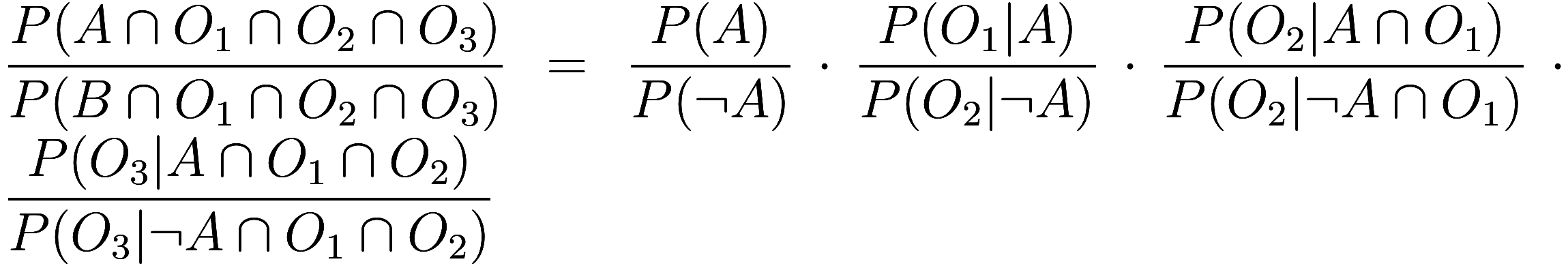

![]() .

.

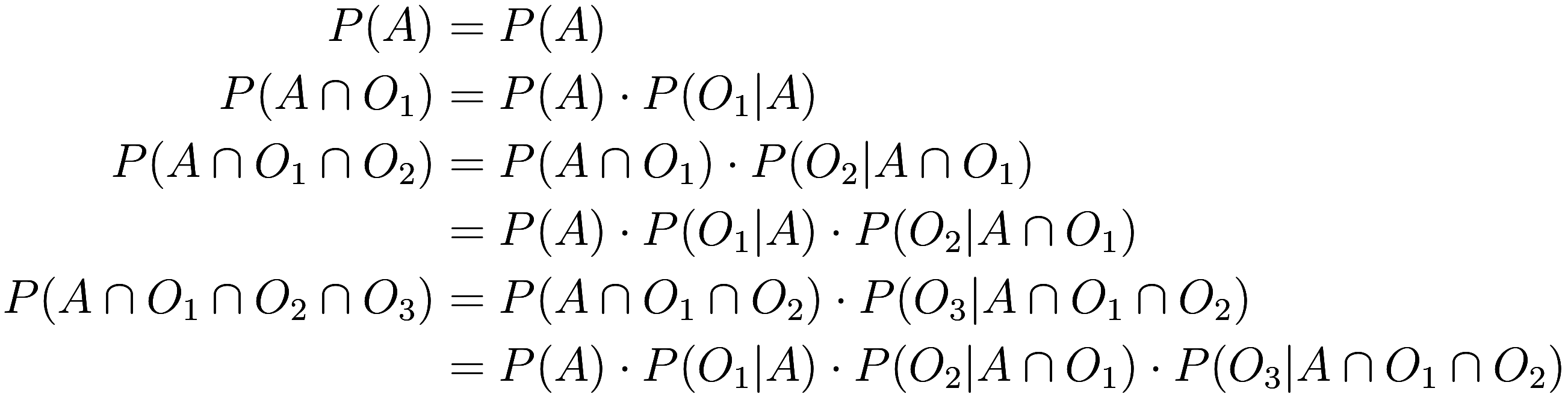

There is nothing deeper to performing Bayesian computation than repeated use of Bayes’ Theorem, but with a little organization we can gain better understanding of the process and be less likely to make mistakes. First, we can build a table of the information we know:

| prior | ||

|---|---|---|

| observation 1 | ||

| observation 2 | ||

| observation 3 |

Because we will be interested in the event that all of the

observations are jointly true , rather than only one or

another of them being true, we have to use the probability of each

observation conditioned on the previous ones also happening. If our

observations are independent of each other then this is unnecessary, as

![]() in this case.

in this case.

Next, let us use the definition of conditional probability:

Thus, the cumulative products we get by just multiplying down the columns of the previous table are the joint probabilities:

| - | 1 | 1 |

| prior | ||

| observation 1 | ||

| observation 2 | ||

| observation 3 |

(Note that mathematically there is nothing distinguishing the prior probability from any of our observations; the choice of what information to call “prior” versus “observation” is just a matter of convention. You can think of prior as the “null” or trivial observation: how much you should update your probabilities based on not making any observations at all.)

We should interpret each row as telling us the relative

probability of either of the hypotheticals jointly with the cumulative observations.

Initially, before making any observations, the prior probabilities

and

sum to 1 but as we apply successive

observations the sum of each row will decrease and become smaller than

1. This residue probability (ie, the amount by which each row sums to

less than 1) represents the chance of some hypothetical alternative in

which at least one of the observations didn’t happen.

Ok, what good has this done us? Well, our goal is to find the

conditional probability ![]() . This is just equal

to the fraction of the

. This is just equal

to the fraction of the th row that is in the first column:

![]()

Indeed, all that matters is the ratio of the two columns:

![]()

Since the columns of the second table were found by just multiplying the columns of the first table, the ratio of the columns of the second table are just the product of the ratio of the columns of the first table:

Thus we began with eight11Actually seven, because we knew ![]() , so the first row only had one data

point. pieces of data in the first table but it turns out

that all we needed was four pieces of data, supposing we can directly

measure these ratios.

, so the first row only had one data

point. pieces of data in the first table but it turns out

that all we needed was four pieces of data, supposing we can directly

measure these ratios.

Indeed frequently the ratio ![]() , called the Bayes

factor, is easier to measure than either

, called the Bayes

factor, is easier to measure than either or

separately; in messy, real-world

scenarios the probability of the event

might be wrapped up with many uncertain factors

that have nothing to do with either

or

. Estimating

requires assessing these irrelevant

factors, but estimating the Bayes factor does not.

In extremes where probabilities get very close to 0 or 1 we can

simplify matters further by taking logarithms everywhere – why multiply

when instead you can add? We then have logarithmic Bayes factors ![]() where

where is the information contained in the

first observation, with positive numbers informing us in favor of event

, and negative numbers informing us against it. If

the logarithm is base 2, then

has units of bits. Adding up each of our pieces

of information gives

![]() (Given a new piece of information

(Given a new piece of information , we can simply add it to the sum we have

so far; this is called Bayesian updating.)

This result is also called the (conditional) log-odds of

.12The

log-odds of

is defined as

![]() , but here we have conditioned on the

observations

, but here we have conditioned on the

observations . Log-odds

can in some situations be more intuitive than ordinary probability,

especially for extreme probabilities. A log-odds of 0 means a

probability of 50%, and positive log-odds means an event that is more

likely to happen than not. From the (conditional) log-odds of

we can compute the ordinary (conditional)

probability:

![]()

How does this work in practice? Suppose some event of interest has some probability of being true; start by

computing the unconditional (ie, prior) log-odds of

. We make a series of observations, and assess for

each observation how much information it provides in favor of

versus against it. We update our log-odds of

by adding to it the information (positive or

negative) from each observation. The result is the updated (ie,

conditional on the observations) log-odds for

. Alternatively, if we don’t want to work with

logarithms, instead of adding up log-odds we can directly multiply

probabilities.

Let us work an example. Suppose you are hiring an engineer, and you

want to know their competency at a particular skill. You make three independent

observations: they did adequately on an interview assessing that skill,

they have an obscure certificate for that skill, and they went to

University of Example which has a good engineering program. Most

candidates, whether competent or not, do not have that certificate nor

went to that university, so it is hard to assess the probability of

those observations; but the relative probabilities, or Bayes

factors, are easier to guess at. We have

| Bayes | log-odds | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| prior | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.111 | -2.2 |

| interview | 0.4 | 0.1 | 4 | 1.39 |

| certificate | - | - | 1.2 | 0.18 |

| UoE grad | - | - | 2 | 0.69 |

| total | - | - | 1.0667 | 0.065 |

Adding up the last column we get a log-odds of 0.065, or a probability of 51.6%, just barely above even odds that the candidate has this particular skill.

This example also illustrates a second important principle to understand with Bayesian reasoning: it can applied to any situation, and always gives an answer, regardless of how appropriate the technique is for the application. I certainly hope no one involved in hiring candidates is using a calculation of this nature to help make that decision, or at least not with the same lack of care as I did above. One must pay close attention to potential problems: did you account for all the available evidence? how accurate are your probabilities? how robust is your result to changes in the data? The messier and more “real-world” your situation, the easier it is to run afoul.

The short answer is very simple: the conditional probability of making an observation conditional on

the null hypothesis

is the p-value of that observation.13Following a conversation

with Michael Weissman in which he disagreed with this statement, I

should clarify that this is only for a binary observation. More

generally one should say that the conditional probability

is related to the p-value, with

the nature of that relationship depending on the definitions chosen for

a particular application.

In Bayesian reasoning we start with a prior probability , a conditional probability

, and the complementary pieces of

information

14Which

of course is redundant with

, since

![]() and

and , and use these to compute an

update:

![]()

In hypothesis testing, the only piece of data we have is the p-value

. We can’t compute

because we don’t have the other required

pieces of data.

If we have all three pieces of information ![]() then it makes sense to go ahead

and compute the updated probability

then it makes sense to go ahead

and compute the updated probability ; however if we do not have access to those

last two numbers, or their accuracy is very low, it can be more useful

to directly report a p-value

and not attempt to compute

.

In primary scientific research, those two numbers are often inaccessible due to two features of the null hypothesis: the null hypothesis being non-probabilistic, and being very narrow or asymmetric.

Suppose is a statement like “it will rain tomorrow”, and

we want to estimate the probability of tomorrow’s weather based on

observing today’s weather. It makes a lot of sense to start with a prior

probability

(based on historic rainfall frequency) and

update it appopriately. But if

is a statement like “neutrinos are massless” or

“fracking does not influence earthquakes” then it is not meaningful to

speak of probabilities like

or

.15Note

that

is still meaningful, so long as the

observation is probabilistic in nature. We could interpret

to mean our level of confidence in

, i.e., as information content, but this often has

more to do with the mental state of the researcher than with

.

Second, Bayes theorem is fully symmetric between and

, but frequently in scientific research these

hypotheses are not symmetric. The classic example is testing if a coin

is fair: suppose we observe 30 heads in 100 coin flips (iid), and we

want to test the null hypothesis

that the coin is fair. Here

is a very narrow and specific claim that lets us

easily compute a p-value

. The negative

is unspecific: the coin has some

bias, but it could be any nonzero amount. The probability

depends on how biased the coin is, so

we need additional information like a probability distribution for the

amount of bias. This is a lot to ask for when we don’t even know if the

coin is biased at all!

Finally, even if we had this extra data and could compute , frequently that is less useful

than reporting raw p-values. Suppose you are doing secondary research,

and want to estimate

; you find that primary research into the

effects of

has identified a series of unrelated observations

that give information about

. Each of these observations has been made by

different research teams with different specialities. If each team

reported their own estimate for

, it would be a troublesome and

error-prone process to combine these estimates into a single value for

![]() : each team will have a

different estimate for

: each team will have a

different estimate for with different assumptions; each team would

incorporate different evidence (perhaps the researchers investigating

the

phenomenon were unaware of the existence of

and omitted it entirely; or the

researchers incorporated some other evidence

that was later found to be unreliable). For you

to compute

would require first undoing all the

computations that each team did to reconstruct the underlying p-values

; much simpler if they just reported

these p-values directly.

The reason primary researchers report p-values is that this is

usually the natural end point of their research; synthesizing the

p-values of many different observations into a single posterior

probability is the job of secondary research. Each probability ![]() might involve a completely

different physical process and speciality, so it is most suitable to

have each term investigated separately by experts in the appropriate

field.

might involve a completely

different physical process and speciality, so it is most suitable to

have each term investigated separately by experts in the appropriate

field.

(Todo; might add some explanatory text on how to convert between bayes factors and p-values)

Recall from the first section that the hypothesis testing method involves three steps:

We slightly glossed over the second step, giving one way to normalize the test statistic by applying its cdf.

Choosing the normalization method is every bit as important as choosing the test statistic (though usually obvious once the test statistic has been chosen); as with the choice of test statistic, any choice is valid so long as the result is uniformly distributed in the range [0, 1], but not every choice might have the same statistical power (i.e., false positive rate).

Recall that we want the p-value to be as low as possible when

conditioned on ; this maximizes the chance of a correct

rejection of

, since we reject when the p-value is below the

threshold. Therefore when normalizing, we first sort all possible values

of the test statistic by how likely they are under the condition of

. Thus, the most likely outcomes will have

the lowest p-values.

Slightly more carefully, what we are sorting by is how

informative each possible value is in favor of over

; that is, we are sorting by the Bayes factors

![]() .

.

For example, suppose our null hypothesis is that a coin is fair, and we observe

that the coin had 30 heads out of 100 flips. Our

test statistic is the number of heads, which when conditioned on

is approximately normally distributed with a mean

of 50 and standard deviation of 5. We can normalize a normal

distribution into a uniform distribution by applying the cdf; then 0

heads gives a p-value of 0, 50 heads gives a p-value of 0.5, and 100

heads gives a p-value of 1. What is the p-value of 30 heads? This is 4

standard deviations below the mean, which we can look up in a standard

normal table is a percentile of 0.00003; that is our p-value, and we

can feel confident in rejecting the null hypothesis that the coin is

fair.

While this worked okay, depending on the application this was not the

best choice of normalization. If instead we observe 70 heads out of 100,

we would have gotten a p-value of 0.99997, and we would fail to reject

the null hypothesis even though we know intuitively that the observation

contains enough information to do so. We would have done better if we

had sorted the possible observations by how informative they are in

rejecting the null hypothesis. Here finding 0 or 100 heads is the most

informative, so they get the lowest p-values, followed by 1 or 99 heads,

then 2 or 98 heads, and so on, ending with 50 heads getting assigned a

p-value of 1. As before, this is done so that the result is uniformly

distributed in the range 0 to 100. Now if we observe 70 heads, this has

a higher p-value than any observation of 0 to 29 or 71 to 100 heads, but

a lower p-value than 31 to 69 heads; therefore it gets a p-value of

0.00006,16The total probability of seeing 0 to 29 or 71

to 100 heads, conditioned on , is 0.00006. again comfortably

rejecting the null hypothesis that the coin is fair.

As we are sorting the observations by their Bayes factors ![]() , this sorting depends on the choice of

alternate hypothesis

, this sorting depends on the choice of

alternate hypothesis . If

is that the coin has any nonzero bias, then

the sorting method we just used is appropriate, and is called a

two-tailed test; but if

is more specifically that the coin is biased

in favor of tails, then the observation of 70 heads out of 100 does not

significantly favor either the null or alternative hypotheses, and so

gets the p-value of 0.99997 we had originally calculated. This is the

one-tailed test. For example, when testing a cancer medication

in rats, our null hypothesis is that it has no effect, and our alternate

is that it reduces cancer rate, so a one-tailed test is appropriate in

that we would not draw any conclusions from an observation of it

increasing cancer rates.17And

also in that rats, unlike certain biased coins, have one

tail. This was an actual question I got from a cancer

researcher who knew how to perform the calculations for a one-tailed and

two-tailed t-test but not which one was appropriate, and only one of the

results was “significant”.18Apparently the group’s statistician was on

vacation at the time; why the researcher thought to ask a 19-year old

kid from a foreign country is unclear. Probably the better

answer would have been that the magical 5% confidence threshold is

arbitrary and no great import should be assigned to whether your results

fall above or below that line.

(A little subtlety: how do we sort by the Bayes factors if we can’t

compute them without choosing a specific bias for ? For the one-tailed coin test, it does not

matter; the sorting is the same for any possible bias even

though the actual values are not. For two-tailed, we have to assume that

bias in favor of heads is equally likely as bias in favor of tails, and

maybe some further assumptions.)

While frequently choosing how to normalize the test statistic amounts to simply choosing between a one-tailed or two-tailed test, in principle it could be any possible normalization scheme: maybe the two tails could be weighted differently, or the sorting goes from inside out, or even numbers come before odd numbers, etc etc. The test statistic doesn’t even have to be a number – all that is required is that it can be sorted by the Bayes factors.

(Addendum. I couldn’t find a decent splash image for this post online, so I asked a bot to draw a picture of “hypothesis testing” and ended up with this mess.)

Follow RSS/Atom feed for updates.