In this part we will use what we have learned about light and temperature to create a simple model of the Earth with its atmosphere, which we can solve to see what effect changing the atmosphere has on the temperature of the modeled Earth.

The model is not quantitative, meaning that it is not accurate enough for the numerical results from the model to agree with the true numbers, but it is qualitative, meaning that the overall behavior of the model agrees with the overall behavior of the Earth. Therefore by understanding how the model works we can improve our understanding of the Earth system; in particular, the way the greenhouse effect works in the model is the same way that the greenhouse effect works on the Earth.

Consider the following figure of the Earth1We mean “the surface of the Earth” when we say “the Earth”, as the interior of the Earth only very slowly exchanges heat with the surface, so it can be ignored. and its atmosphere, with energy flowing between them.

The arrows in the diagram represent energy flowing between the

different objects in the form of light; we ignore other forms of energy

transfer2All energy exchanged with the Sun or with space

is in the form of light, but some of the energy exchanged between the

Earth and the atmosphere is in other forms. In particular, hot water

molecules that physically move from the surface into the air bring a

large amount of energy with them, called latent heat. Heat

conduction plays a lesser role. We also omit geothermal heating, which

is energy flowing from the interior of the Earth to the surface. This is

estimated to be 47 TW, or 0.092 watts per square meter..

On the left of the diagram is shortwave radiation, that is, visible

light. The variable is the rate at which energy from the Sun is being

absorbed by the surface of the Earth; we assume that none of this

shortwave radiation is absorbed by the atmosphere. We omit from the

diagram light from the Sun that strikes the Earth (or clouds in the

atmosphere) and is reflected to space;

is only the portion that is absorbed. Recall from

part 3 that

![]()

On the right of the diagram is longwave radiation, that is, infrared

light. The variable is the rate at which radiation leaves

the top of the atmosphere to space; some of this is emitted by the

atmosphere, and the rest is emitted by the Earth and passed through the

atmosphere. The variable

is the rate at which radiation

emitted by the atmosphere strikes the Earth. Finally, the variable

is the rate at which radiation is emitted by the

Earth, which will either be absorbed by the atmosphere or transmitted to

space.3We briefly remark on the arrows that are absent

from the diagram. The most interesting omission is the arrow from the

Sun to the atmosphere; we have already commented on that. A tiny

fraction of the light emitted to space goes on to strike the Sun or

other bodies, but we are uninterested in where exactly it goes once it

leaves the Earth. Space is filled with cosmic microwave background

radiation, so there should be arrows representing microwave light

from space to each of the other objects, but the amount is so tiny as to

be totally insignificant – only 1.6 GW of it reaches the Earth, or 3

microwatts per square meter. Finally, the Sun emits a tremendous amount

of light into space that does not strike the Earth, but we are not

interested in that.

As discussed in part 3 we are interested in the equilibrium of the system, that is, when the total amount of energy entering each object equals the energy leaving that object.

So far we have not made any assumptions about the physics of the atmosphere, so there is insufficient information to solve for the model’s equilibria. However before we go further let us look at what we can conclude so far.

Let be the average4Whenever we say the “average” temperature of a

(spherical) object in the context of blackbody radiation, we mean the

fourth root of the arithmetic mean of the fourth power of the surface

temperature, weighted by surface area and emissivity. That is, we use

exactly the average that makes the Stefan-Boltzmann law work with the

result. For objects like the Earth, where the temperature does not vary

tremendously from one location to another, this average is close to the

ordinary arithmetic mean. For tidally-locked or slowly rotating objects

like Mercury or the Moon, the distinction can be very

important. temperature of the Earth. Then as before, we

know that

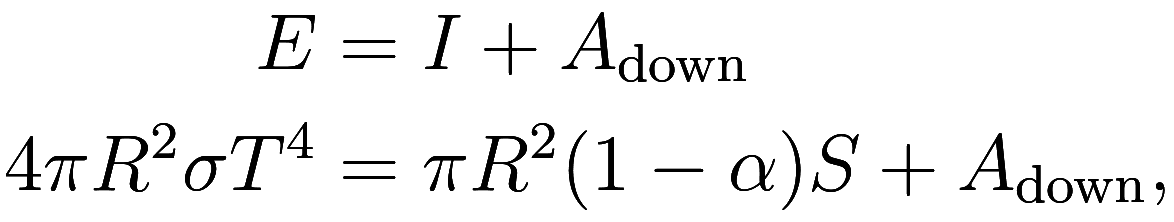

![]()

where is the radius of the Earth.

At this point in the calculations in part 3 we solved for the

effective temperature that satisfied the equality

. However, the introduction of the atmosphere

changes this equation. Since the Earth is at equilibrium, the total flow

of energy in and out of the surface is equal, giving the equality

where the additional term is downward heating from the

atmosphere, which has the effect of increasing the temperature

of the surface of the Earth, demonstrating the

greenhouse effect. Our goal is to find the temperature

of the Earth, which will require calculating

and

.

Since the atmosphere is at equilibrium, we also have

![]()

Combining this equation with gives us

, which is to say that the total

amount of sunlight the Earth absorbs equals the total amount of light it

emits, much as we would expect5In

fact, direct measurements of light going in and out of the Earth agree

with each other up to the accuracy with which they can be

measured..

To solve for the temperature of the Earth, we need the values of

and

, or equivalently we need to know what

fraction of the energy

emitted by the Earth is absorbed by the

atmosphere or transmitted through it to space. We know that

![]() but that is not sufficient

information by itself. To find these values we need some kind of

additional assumption about the physics of the atmosphere.

but that is not sufficient

information by itself. To find these values we need some kind of

additional assumption about the physics of the atmosphere.

The simplest assumption is the total absence of gases that interact with infrared light, so that the atmosphere has no greenhouse gas. In this case, all light from the Earth is transmitted directly to space, and the atmosphere neither absorbs nor emits any infrared light.

In this case, we have and

. Then

and we get exactly the situation of part 3,

so that the temperature of the surface of the Earth equals the effective

temperature:

.

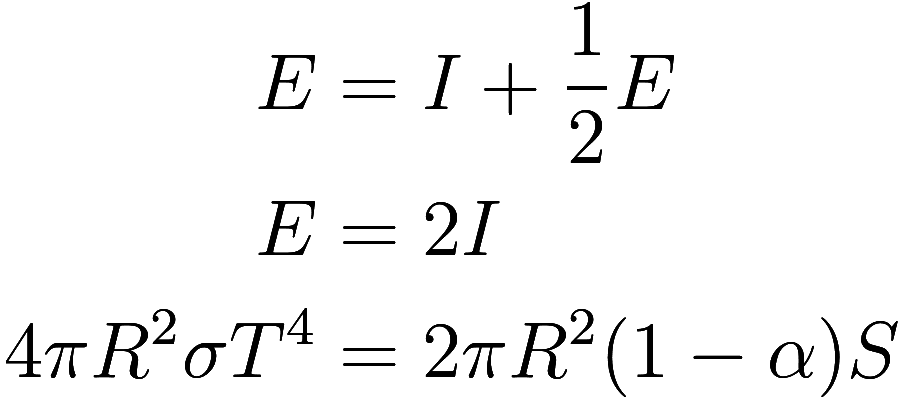

The next simplest assumption that can be made about the Earth’s

atmosphere is to assume that it fully absorbs all upwards emissions from

the Earth while maintaining a single uniform temperature, which is

usually described by saying it has a “single layer”. Thus consists only of emissions from the

atmosphere. As the atmosphere has a uniform temperature, it emits the

same amount of energy upwards and downwards, so we get

and

![]()

Combining with we get

so

![]()

This is 30 C or 86 F, somewhat above the true average temperature of the Earth.

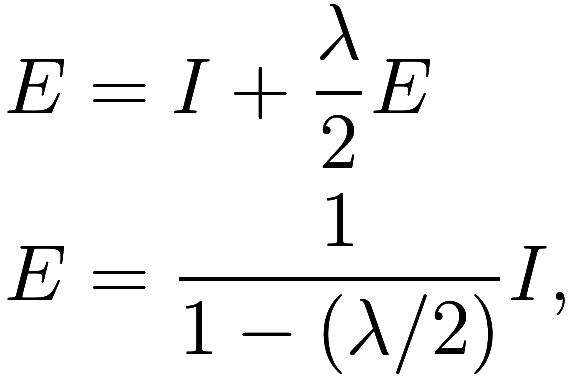

Let us assume again the the atmosphere is a single layer of uniform

temperature, but now suppose it does not have sufficient greenhouse gas

to fully absorb all infrared emissions from the Earth. Let be the fraction of such emissions that are

absorbed, so that the atmosphere absorbs

and transmits

. Since half of the atmosphere’s

emissions are downwards (by the uniform temperature assumption again),

we get

![]() , so that

, so that

and therefore ![]() .

.

When , we recover the situation of the model

with no greenhouse gas, and get

. When

, we find again the result of the model

with ample greenhouse gas, and get

. As we vary the amount of

greenhouse gas in the atmosphere from none to ample,

varies between 0 and 1, and the temperature

calculated from the model varies from

to

, increasing as greenhouse gas is added.

This illustrates how adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere causes

the temperature to rise.

With the single-layer assumption we saw that the Earth’s temperature increased with additional greenhouse gases up to a fixed maximum. However, as more and more greenhouse gas is added to the atmosphere, the assumption that the atmosphere can maintain a uniform temperature would break down as the emissions from the Earth can’t penetrate past the very bottom of the atmosphere.

If we instead approximate the atmosphere as being composed of

multiple layers, each fully absorbing all incident infrared radiation

and individually have uniform temperatures, then each such successive

layer of greenhouse gases causes the temperature to increase by a factor

of . Equivalently, every fourth layer doubles

the temperature.

Similarly, we could modify the model to accommodate anti-greenhouse

gases6Hazy conditions can have an

anti-greenhouse-like effect, although the mechanism is not exactly the

same; for example, major volcanic eruptions cool the Earth for a few

years by putting sulfur aerosols in the stratosphere.

which absorb shortwave radiation and transmit longwave radiation. Each

such layer of anti-greenhouse gases decreases the temperature by a

factor of , countering the effects of one layer of

greenhouse gases.

Follow RSS/Atom feed for updates.